Consumption report: If it’s not violent and perverted, I’m not interested

Lately I’ve been reading the manga Dorohedoro, which involves a lot of violence. But the impact is blunted because of the sheer volume of it, and also ’cause of how apparently easy it is for characters to be healed or resurrected through the use of certain magic. The manga is a science-fiction/fantasy drama about the conflicts between magic users and humans. It starts off with a half-humanoid half-reptilian amnesiac named Kaiman who’s had his head magicked into that of a reptile by a magic user, and so he roams his human dimension (Hole) hunting magic users to find the one who hexed him. Magic users often cross over from their world into Hole to use humans as target practice for their magic, so there’s a lot of animosity between the two species. It starts off in this way, but the deeper you progress in the series (and I am currently only half-way through), it becomes more about the conflicts between different magic users; I guess because it’s more interesting when magic is involved.

The art style is very sketchy and raw, which I like, and it really makes the gory scenes look all the bleaker. Sometimes the artist just makes a dark rough scribble on the page and it looks terrifying. There are many detailed drawings of eviscerated and mutilated bodies, and many scenes in which body meat is just used as a prop or decoration. One of its main characters is a man who wears a heart-shaped mask in the form of an anatomical heart. It’s not for want of detail or even accuracy that the images don’t gross me out that much, but that injury and death are so inconsequential within the larger story. Eventually, you get to a point where if a character is killed, you don’t really expect them to remain dead for long!

Here’s the typical rule of manga, which I thought was only true for basketball stories, but which I’m starting to see is pretty true across the board. Something always seems like the worst imaginable thing that could happen, until it happens, and then there’s another next worst imaginable thing to be scared of. The form remains driven by plot and action rather than psychology, even when it tries very hard to be a “psychological drama”. It can’t be helped: due to the nature of the form, the amount of blank panels that have to be filled up with something, things just keep needing to happen. Most things in manga are totally gratuitous, so even the violent stuff ends up being kind of tedious after a while.

A few days before embarking on Dorohedoro, I watched Takashi Miike’s Visitor Q which I saw someone on twitter recommending as a film that they’d never watch ever again. (Well, people like me take this as a recommendation anyway.) Visitor Q is a direct-to-video film that explores, to a literal extreme, the Oedipal psycho-drama of a single, estranged family. Here’s a brief summary of their sins: journalist father who’s constantly on the lookout for the next sensationalist phenomenon even if it involves irreparable harm to his family; prostitute daughter who sees all men as opportunities for cash, even her father; bully victim son who takes out his frustrations at school on his mother; and diminishing mother who is caned daily by her son.

It’s not gory. It’s just conceptually disgusting. So if you’re not the type who can separate representation in art from reality, then I guess it would be unwatchable; but on the whole, it’s totally watchable so long as you see it all as some kind of fable about family bonds and maternity. These are the sorts of conflicts that would totally destroy a society if they took place in real life, and so art remains the only realm where they can be dramatised. Like how Dorohedoro’s gratuitous violence had a roundabout effect of totally blunting its own impact, then Visitor Q’s extreme levels of perversity actually end up becoming a form of family solidarity.

Its closing sequence can be interpreted as a parable about the ultimate and unique power of familial love; the people who cause you the most pain can also give you the most gratifying feeling of love, etc. It’s a tender unravelling, like a run-on sentence in a Robert Montgomery artwork: “Echoes of voices in the high towers all wounds explained here all knives bandaged all empires arrested all castles unbuilt all hearts unbroken”. But actually, if you think about it… yeah, it’s still fucked up. In the end, the family’s problems are only solved through bestial murder and the mother’s miraculous ability to produce breast milk again. The final scene is of mother, white as a ghost, smiling seraphically as her family suckles at her breasts. The family chooses to abandon their individual existences and return to the primal soup of non-differentiation, i.e., the womb. Or LCL, as they call it in Neon Genesis Evangelion.

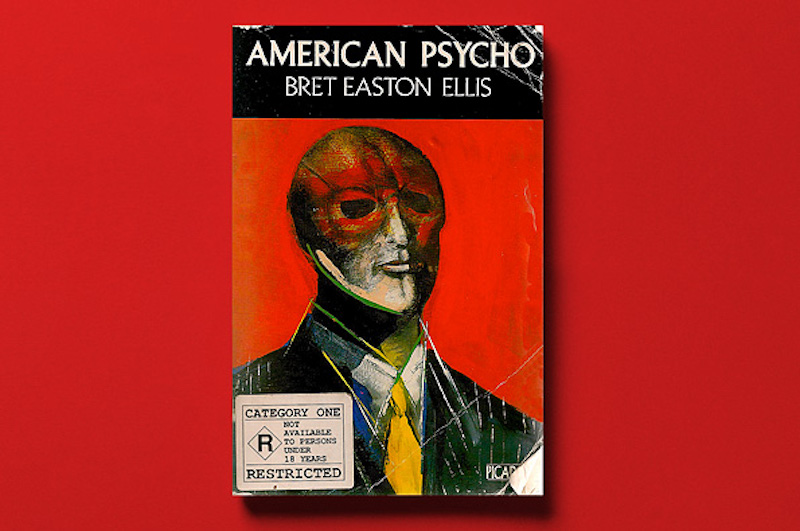

Last month, I finished reading American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis, who is probably my most-read writer for this year. Unlike Dorohedoro, I don’t believe that the violence in American Psycho was gratuitous, but, like Dorohedoro, it is so overblown and drawn-out that it’s difficult to believe in for long. The victims somehow miraculously remain not only alive but also conscious while Patrick Bateman performs every imaginable torture on them. Unlike Visitor Q, it’s actually pretty gory despite its surrealism, and you might end up flinching even if you’ve got nerves of steel and an indomitable ability to separate art from reality.

I’d already watched the movie earlier this year, when I had started on my Bret Easton Ellis kick but was still too afraid to read American Psycho just yet. The movie really played up the idea of it being a social critique of Wall Street. My version of the book (Vintage) comes with an afterword at the end where Bret Easton Ellis shakes his fist at the hysterical feminists who tried to get his book cancelled. But one very clarifying point he makes in the afterword is that the book is not entirely about toxic masculinity, or violence against women, or even about Wall Street bankers necessarily, but about himself, at a very dark and alienated time in his life.

Yes, he did spend a lot of time snorting coke with bankers as “research”, but the book feels too psychologically tormented and haunted to just be a piece of satire. To understand where Patrick Bateman’s chaotic instability comes from, you don’t need to know the world of Wall Street or the banking class that much. Just because Patrick Bateman dresses in Ermenegildo Zegna and Armani, it doesn’t mean that the book is a critique solely of those things.

While I do think the extent of Patrick’s rage is uniquely due to his position, especially as a white, male, upper-class, closeted metrosexual with a horrifically boring life, American Psycho still speaks to a universal narcissism that comes part and parcel with living in a post-modern, post-religious, post-family, post-Sixties capitalist city. The narcissism is one for a society of people who live completely individuated lives, chasing their own status, with style and personality pretty much being subsumed into certain “categories” of images, so that even punk or bohemian rebellion is just another style of conformity. Memories of Patrick’s mother, father, and brother flit by without context in the haze of his murderous breakdowns.

The reason that Patrick is constantly mistaken for other people is because he is a mirror of other people and so has no stable sense of self. He could be anyone, including you, regardless of whether you’re a Wall Street suit or not. It’s a tale that reverberates with Raskolnikov’s in Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment—only he kills the prostitute in this one. In a society of individuals living entirely for themselves, for the next season’s trends, for the next bump in a bathroom, and for the next tepid thrill, no one really matters and everyone and their hopes and dreams are interchangeable.

Within a decadent society, sadism soon starts to creep in because justice and conscience have failed, and progress is stalled. Real evil and egotism go unacknowledged in society, let alone unpunished, and there are no remaining avenues for redemption. In the end, everyone thinks Patrick’s just joking around.

Visitor Q was a family drama; American Psycho expands it to all of society. A scene may open with all the men composed, having a tediously repetitive conversation in a bar called Harry’s, and then the curtain is pulled back and the world is drenched in blood and guts, writhing with bodies like in Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom; we’re in hell, Patrick’s running through the rooms after a prostitute so he can rip her head off with his teeth, like in Bouguereau’s painting. In Visitor Q, the danger was non-differentiation in the form of a return to the infinite womb. In American Psycho, rather than the self liquefying into blank eternity, it is rather that the only thing that exists eternally is the self. The world is a hall of mirrors, and Patrick is a mirror reflecting back an infinite self, which is an abyss.