2025, The River Kwai

This "whistle march" scene from The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

The video above shows how I am attempting to march into 2025: a prisoner of a (spiritual) war, forced (by the system) into labour, building bridges only for them to be blown up, struggling to maintain my last shred of dignity whilst trapped in the stultifying tropics, harassed by diabolically neurotic and demanding Asians!

OK, happy new year. I'm joking. But isn't this a stirring opening scene, and isn't this how everyone wants to live their life? In control of their situation, rather than tossed about by the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Isn't the building of the Burma-Thailand Railway, a.k.a. the "Death Railway", by hundreds of thousands of Allied prisoners of war during the Japanese occupation a more noble, momentous act than any of the small and silly actions we partake in daily within a "free" "peaceful" society?

David Lean's 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai is a highly entertaining piece of historical fiction set in the Pacific theatre of World War 2 about Allied (mostly British + American) prisoners of war, captured by the Japanese and forced to work on their captor army's plans of a bridge from Myanmar (or Burma) down to Singapore to facilitate the transport of supplies throughout the Japanese occupied territories. In particular, the movie depicts the unwavering grace and dignity of the British military spirit, encapsulated by its leading man, Colonel Nicholson (played by Alec Guinness, a recurrent star in David Lean's movies) who leads his regiment in building a railroad bridge over a river in the middle of the Siamese jungles. In the process, he is, variously, locked up for weeks in a metal cage without food, screamed at by his counterpart on the Japanese side, Colonel Saito who is under pressure to build this railroad within an unrealistic frame of time, he is plotted against, his workers question his loyalty to his nation, but nevertheless he leads his men with dignity through their forced labour to perform the technical feat of building a railroad bridge in the middle of a foreign tropical territory where previously there was just mud and malaria.

Over the Christmas holidays, I took a week-long vacation to visit Thailand, specifically Kanchanaburi, the district bordering Burma where the historical "Bridge on the River Kwai" is located. Here are some photos:

The views of the Kanchanaburi town centre.

I took the old-school, aircon-less train that departs twice daily from Thonburi train station in Bangkok to Kanchanaburi train station, located in the urban centre of the district. It was a hot, sultry late noon train that gave me sunburn. There were wide open windows for cross-ventilation, aided by weak and dust-covered fans on the ceilings, some of which weren't working. The interior of the train was vintage but clean, the walls were painted a cheery orange that still looked fresh, the seats were facing wooden benches. The journey took a little over 2 hours and passed through various scenes of the Thai countryside, mostly paddy fields. The Thai climate is very dry; daytime is searing sunshine unabated by rain or clouds, nighttime is cool breeze and a dramatic decrease in temperature.

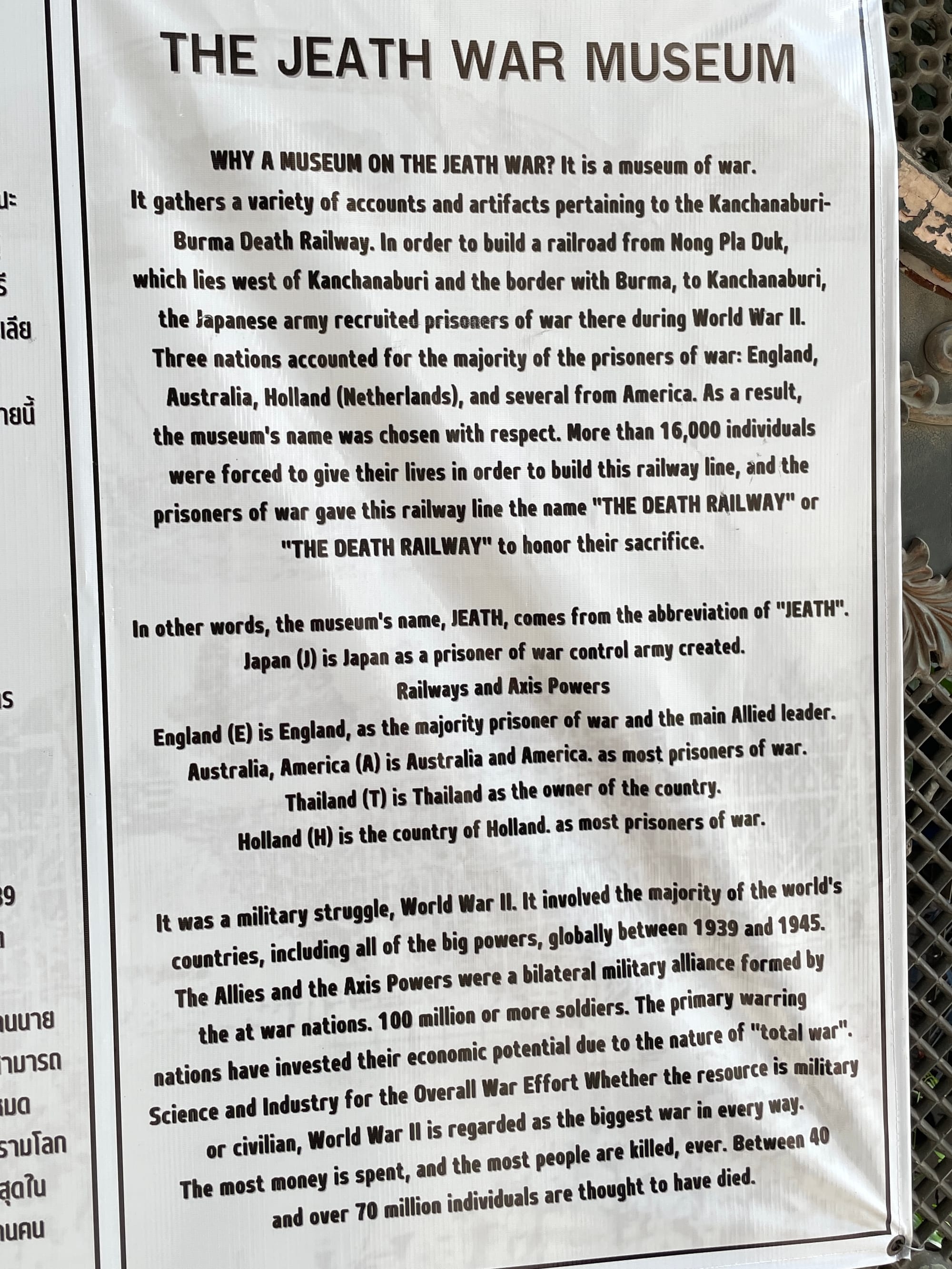

I spent two days in the Kanchanaburi town centre, where I visited two museums dedicated to the memorial of the prisoners of war who worked on the "Death Railway". One was founded by a local Thai abbot and the other was founded by an Australian historian. The "JEATH War Museum" is located on the grounds of a temple near to the bridge on the River Kwai. Contrary to one's first impressions, its title is not a typo but rather an acronym, as this introductory signage at the entrance of the museum explained to me:

The JEATH War Museum hosts a few dusty artefacts and dioramas related to World War II (and also some related to Kanchanaburi's significance in pre-history?), with haphazard sign-posting and captioning. The museum's grounds in general is a strange mix of several buildings, including the history museum, the temple-chapel, and a medieval-style fortress/pavilion. I won't go into too much detail here – briefly, the chapel is a shrine to the Buddha, and the fortress is, erroneously, a historical museum dedicated to general Thai history, with illustrations and narratives painted all over the walls up to the ceilings.

Left: The chapel-temple. / Right: The view inside one of the fortress's many rooms filled with historical scenes from Thai history, painted on all the walls up to the ceilings.

The views from the top of the fortress.

The Death Railway Museum and Research Centre is located more centrally in the town centre, a short walk away from the train station. It has a more cohesive, sober, imitation Roman look. Right across the small road outside is a large, well-kept cemetery home to the graves of various regiments of Allied POWs, their headstones shaded by tall trees and shrubs of local flowers.

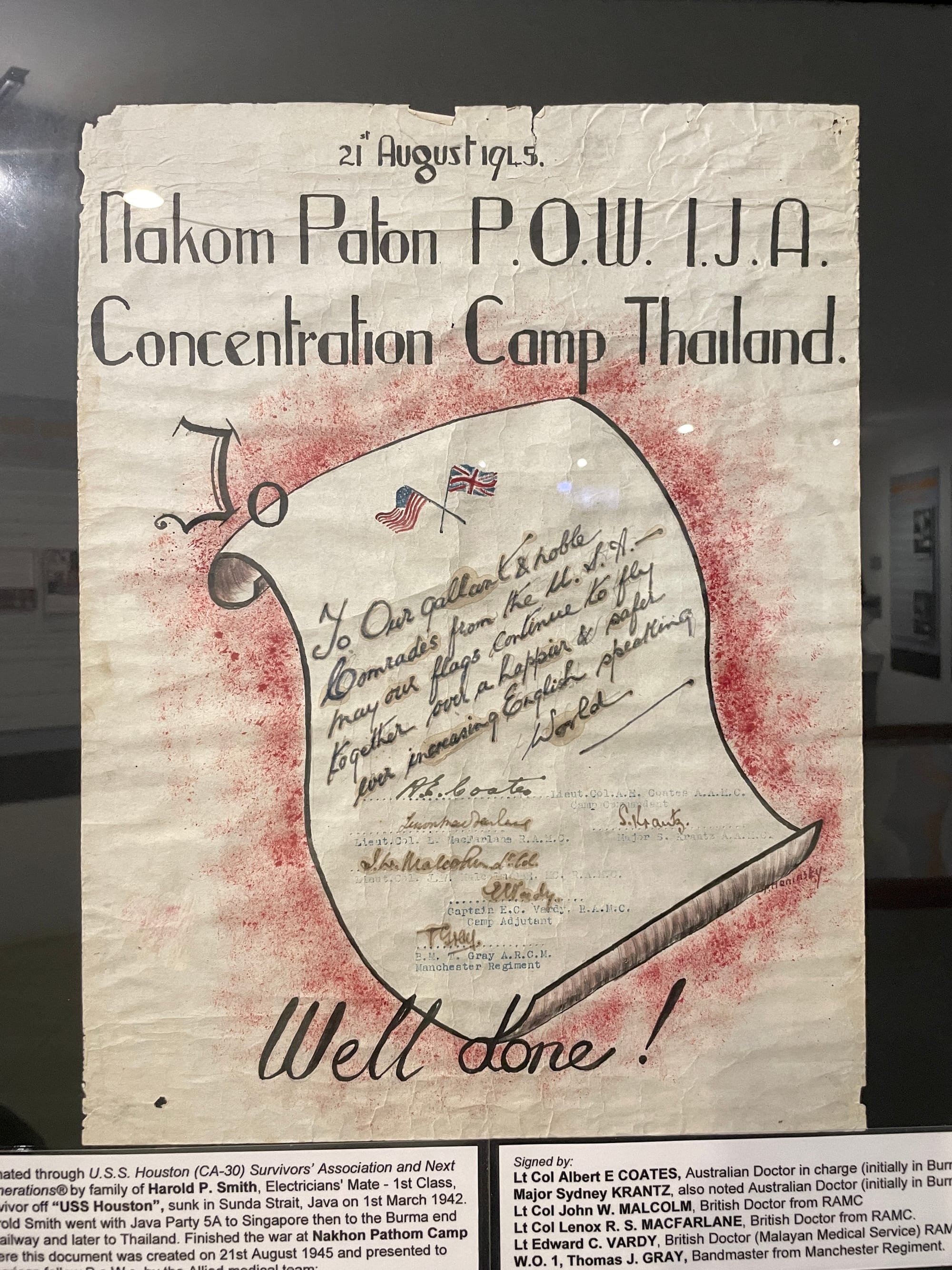

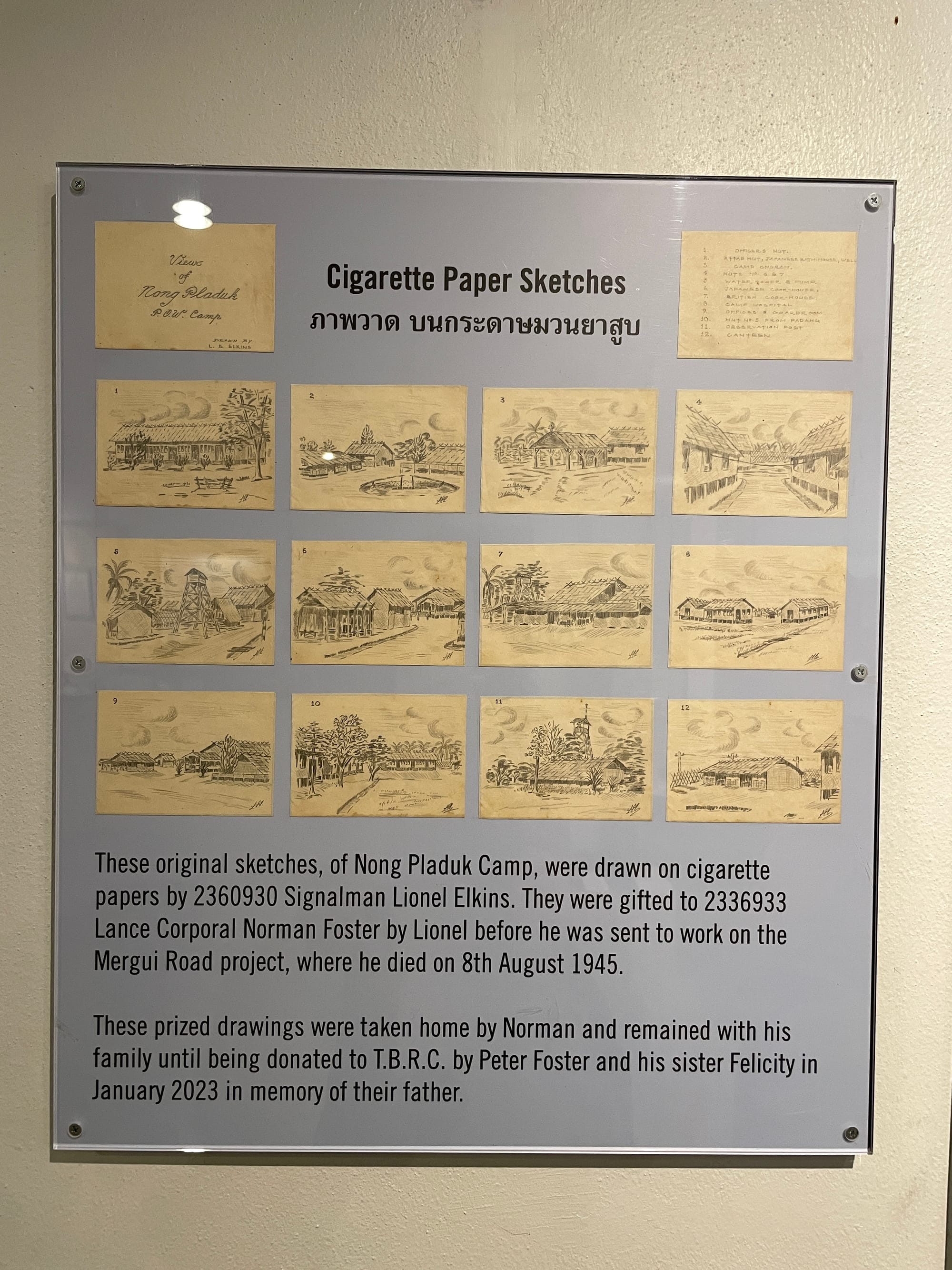

The Death Railway Museum and Research Centre offers quite a comprehensive and at times moving look into the history of the railway. The museum contained dioramas and statues built with funding from various Allied governments or memorial funds, and their artefacts numbered quite a large amount of donations from prisoners' families. Notably, it was only the Allied prisoners of war who left documentation and records of their time on the railway and of each other. A sad and dumb absence in the museum is that of any documentation of the tens of thousands of Malayan slaves/indentured labourers (of which included Malays, Tamil coolies, and some Chinese coolies too) who worked and perished in greater numbers than the Allied prisoners on the railways.

A stained glass window in the Death Railway Museum & Research Centre. The window depicts a scene from the memoirs of an Allied soldier, about a cruel Jap who hits a British prisoner who offers water to a weak and wounded Jap soldier !

Memories from the war and the camps.

Once you visit both railway museums, it's obvious which one was founded by a local, and which one founded by a foreigner invested in local history. The "JEATH" War Museum, aside from its ridiculous name, has the overall feeling of a junkyard. Despite the intricacy of the paintings that trail all over the walls, their presence in the "museum" is just plain random. The artefacts are all dusty, and the display of old WW2-era currency had a large sign stuck on the vitrine proclaiming, "SELLING OLD CURRENCIES - ENQUIRE FOR PURCHASE - WANT TO BUY LAND."

Why, despite their numbers, did the Malayan prisoners not leave a single trace on the memory of the Death Railway? The cynical and ridiculous answer might be that their records were "suppressed" or they were discriminated against as less important, but it's clear that the task of documentation depended on the initiatives of the prisoners and their regiment leaders, and the Malayan labourers simply didn't have the knowledge or literacy to do so, nor was there anyone around to do it for them. Some things, I guess, reverberate into the present day. The "JEATH" War Museum is a similarly stupid and unfocused memorial; founded by a local – whose people were never that impacted by the Railway, seeing as they weren't occupied by the Japanese – who seem to have had some spare land for displaying and storing some of the historical artefacts that had built up around the area.

I start the year thinking about this Bridge, this movie, and these museums, because I'm desperate to know that there are better ways of existing in this world and commemorating the passage of time. Even if you are a prisoner in some camp in the middle of a tropical backwater – which most of us now aren't, but probably still are in spirit – the options are still open for you as to how to conduct yourself with dignity towards a meaningful posterity. And yes, I know how the movie ends. All is vanity, petty squabbling over the build-up of small misunderstandings, but I think I'd prefer this - vanity, war - over anonymity and tropical stupefaction.